|

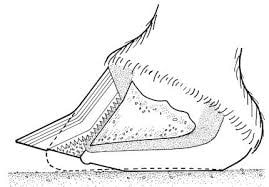

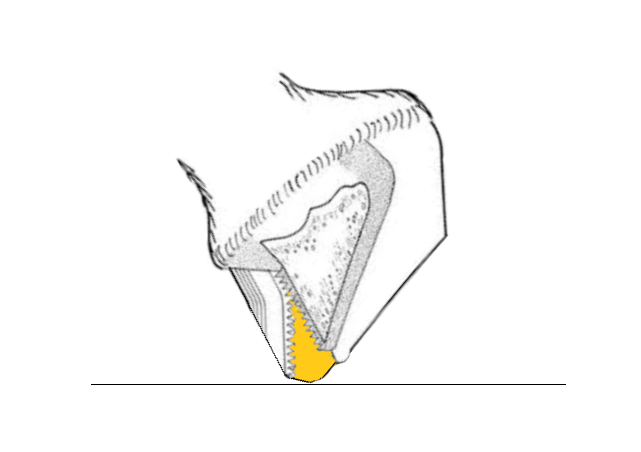

Maintaining a horse's hooves is vital for their overall health and performance. Among the many aspects of hoof care, trimming the frog holds a special significance. The frog, that V-shaped structure in the center of the underside of the hoof, plays a crucial role in shock absorption, traction, and blood circulation. Properly trimming the frog not only ensures the horse's comfort but also prevents potential issues like thrush and caudal hoof pain. In this guide, we'll delve into the essentials of trimming the frog effectively, drawing insights from barefoot experts like Dr. Robert Bowker and Pete Ramey.

In conclusion, trimming the frog is a critical aspect of horse hoof care that requires attention to detail and a thorough understanding of equine anatomy. By following proper trimming techniques you can ensure optimal caudal hoof health for your horse. Consistency and attention to detail are key in maintaining healthy hooves and preventing potential issues down the road.

0 Comments

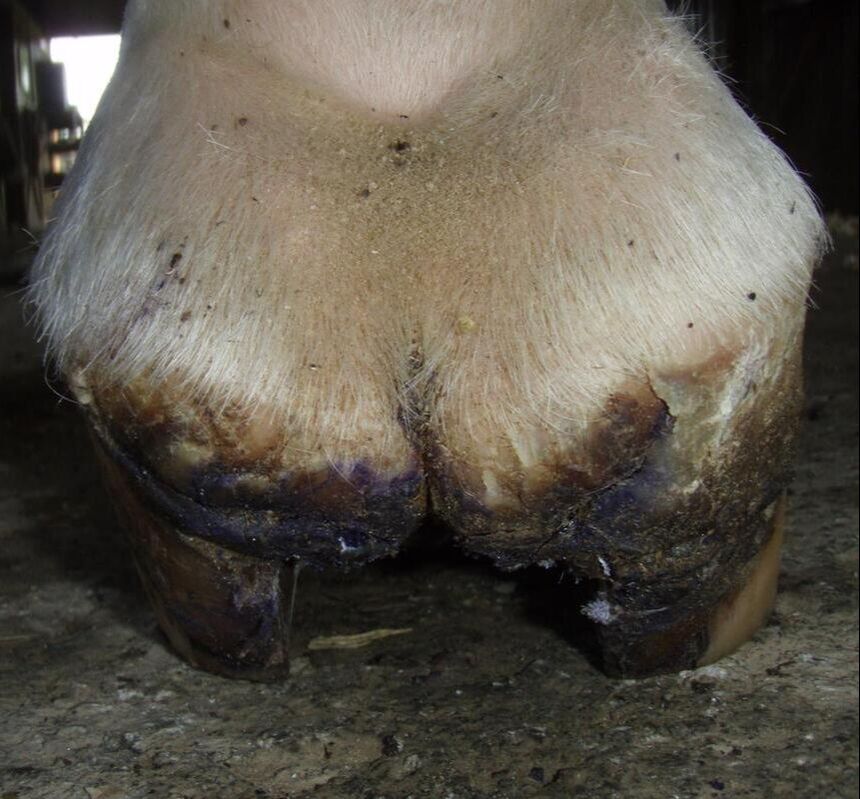

Peripherally Loading the hoof and prolapsed frogs, the pitfalls of traditional shoeing techniques4/14/2024 The concept of peripherally loading the hoof is not really something most barefoot trimmers endorse. While this approach aims to shift weight-bearing forces away from the internal structures of the hoof, such as the digital cushion, frog, and coffin bone, it can inadvertently lead to a host of issues, including a weak digital cushion and prolapsed frogs.

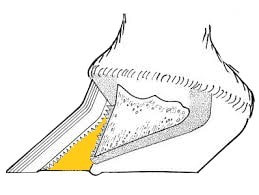

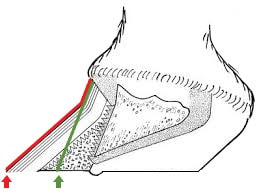

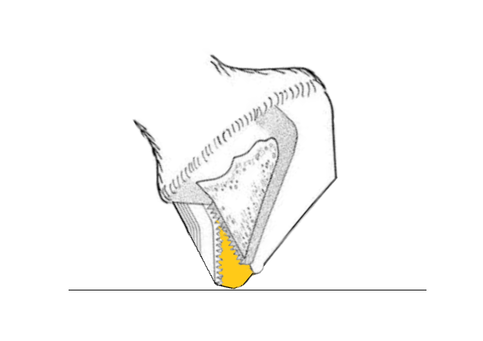

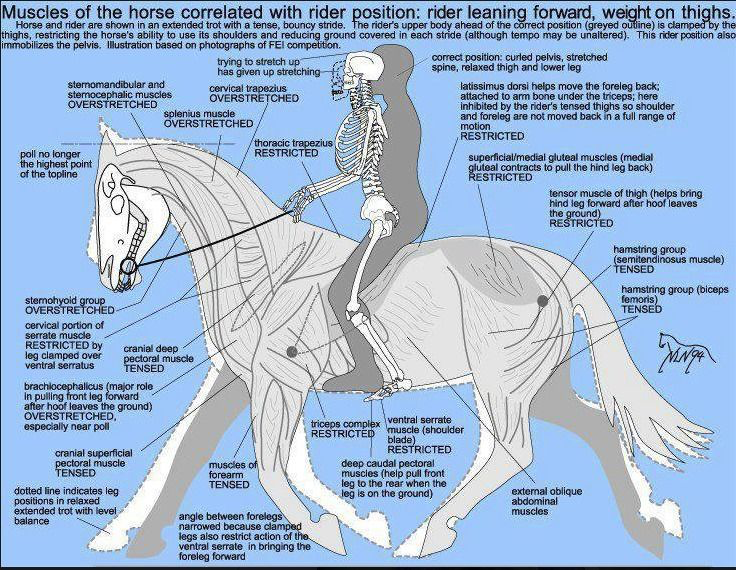

Peripherally loading the hoof involves applying excessive pressure to the hoof wall, often through the use of shoes or improper trimming techniques. While the intention may be to alleviate strain on the internal structures, such as the coffin bone, navicular bone, and tendons, it can result in unintended consequences. One such consequence is the prolapse of the frog, where the frog tissue becomes compressed and displaced downward due to inadequate support and stimulation. Prolapsed frogs occur when the frog tissue, which plays a crucial role in weight distribution and shock absorption, becomes weakened and fails to maintain its proper position elevated up within the hoof capsule. This can lead to discomfort, lameness, and compromised hoof function. These horses will be very sensitive in the back of the hoof and can land toe first instead of heel first, and suffer from caudal failure if left untreated. Rehabilitating a hoof with prolapsed frogs requires a multifaceted approach that addresses both the underlying causes and the structural integrity of the hoof. Central to this approach is the careful stimulation and rebuilding of the digital cushion and frog tissue. By focusing on these essential components, we can help restore proper hoof function and mitigate the risk of further damage. First treat the frog for thrush, as the protecting structure for the digital cushion the frog needs to be the priority. Second, carefully bring the frog into a weight bearing state either barefoot, with boots and pads or with the use of soft hoof packing and composite shoes with frog support. The digital cushion serves as a critical shock absorber, dissipating the impact forces generated during movement. When peripherally loading the hoof, this vital structure may become underutilized and weakened. To counteract this, it's essential to implement strategies that encourage the development and strength of the digital cushion. This can include exercises that promote natural movement and weight-bearing, as well as proper trimming techniques that support healthy hoof function. Often the horse will learn to land toe first because of pain in the back of the hoof, but even as you remove those sources of pain the muscle memory will keep the horse landing toe first unless you also rehabilitate the body with postural changes and bodywork. Ultimately, the rehabilitation of prolapsed frogs is not just about restoring hoof health—it's about safeguarding the overall well-being of the horse. By prioritizing the stimulation and development of the digital cushion and frog tissue, we can help dissipate impact energy, protect the horse's joints and body, improve and restore correct biomechanics and promote long-term soundness and comfort. In the world of hoof care, one of the most intriguing and vital structures is the digital cushion. Often overshadowed by discussions of the hoof wall or frog, the digital cushion plays a pivotal role in maintaining hoof health and soundness, particularly in barefoot horses. Let's explore what the digital cushion is and why it's so important for equine comfort and performance. Understanding the Digital Cushion The digital cushion is a unique, elastic structure located within the back of the horse's hoof. It serves as a shock absorber, cushioning the impact forces generated with each stride. Composed of specialized fibrous and fatty tissue, the digital cushion is designed to compress and expand, effectively dissipating the energy generated during movement. Primary Function: Absorbing Impact

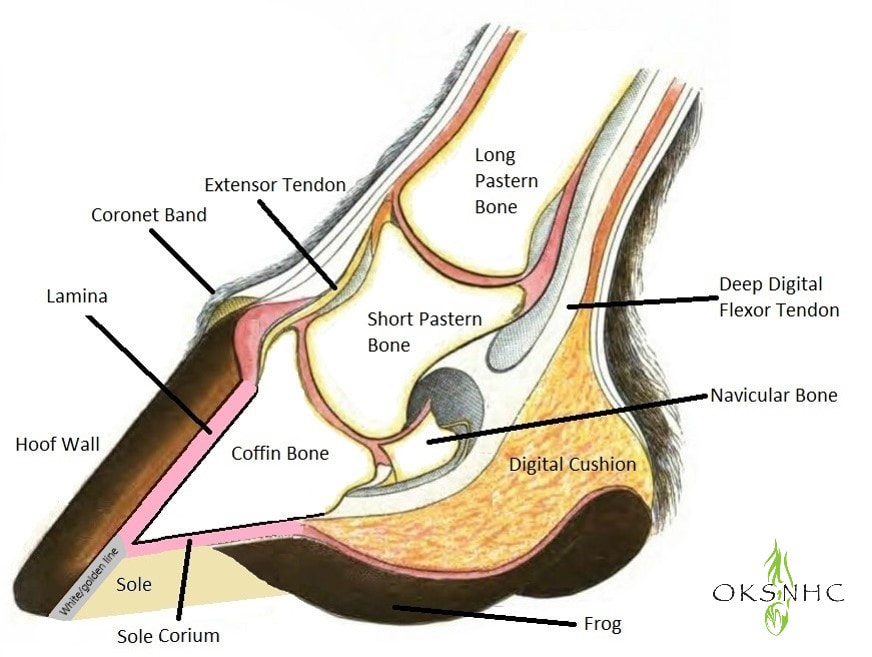

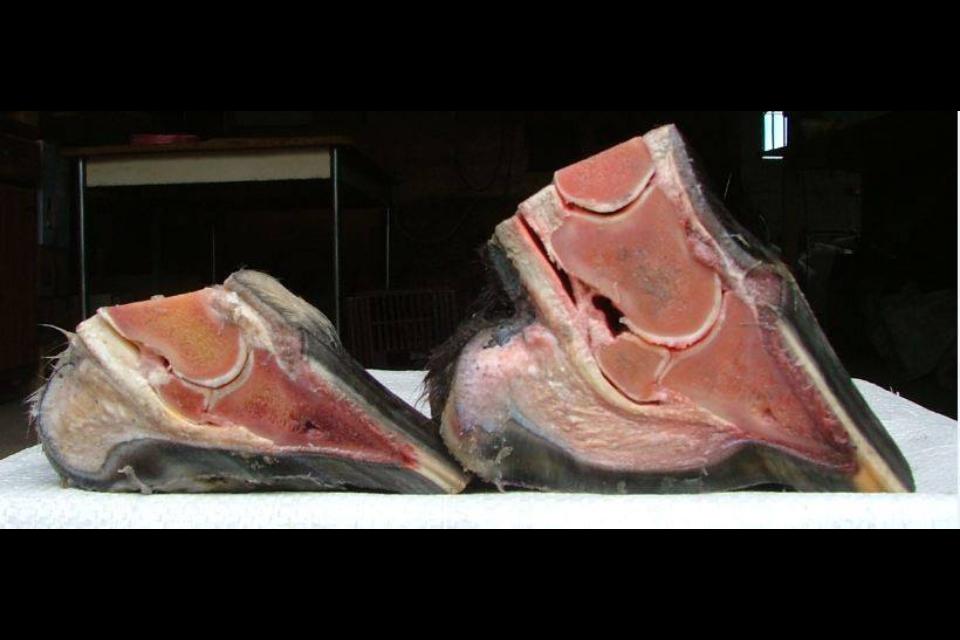

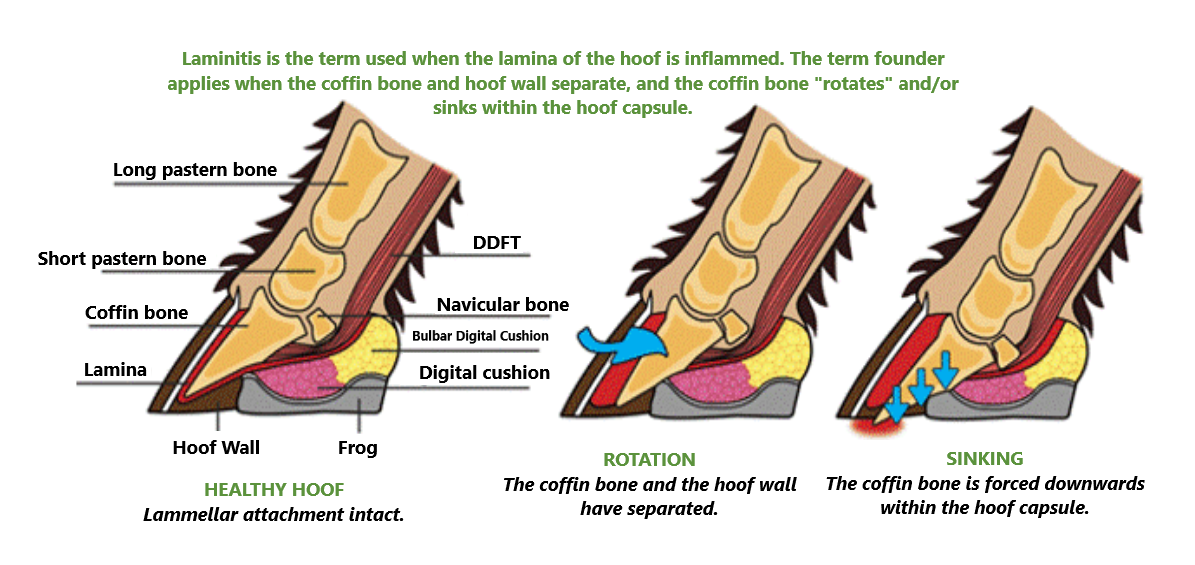

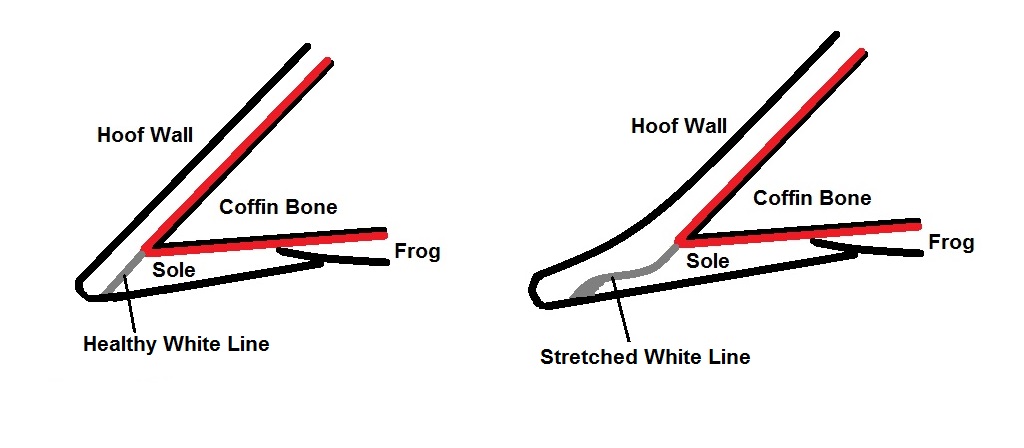

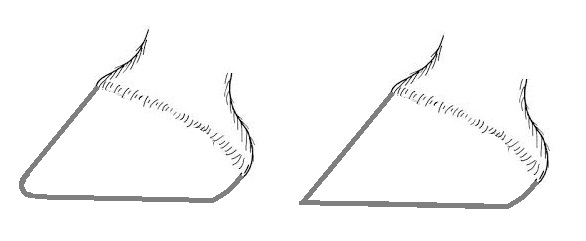

At the heart of its function lies the remarkable ability to absorb impact. When a horse moves, the force exerted on the hoof is considerable, especially during high-impact activities. The digital cushion acts as a shock absorber, reducing the impact energy on the hoof structures and lower limb joints. It serves as nature's built-in shock absorber, ensuring the horse can move comfortably and efficiently. The Role of the Frog Often referred to as the "heart" of the hoof, the frog is closely intertwined with the digital cushion. While the frog itself provides traction and assists with blood circulation, it's essentially an extension and protector of the digital cushion. The frog helps distribute weight evenly across the hoof, promoting healthy function of the digital cushion and ensuring optimal shock absorption. Keeping the frog healthy is hugely important so that it can protect the digital cushion and deflect impact energy to it. From a barefoot perspective, maintaining the integrity of the digital cushion is extremely important. Unlike shod horses, which may rely on artificial support and peripheral loading from metal shoes, barefoot horses depend on the natural resilience of their hoof structures, including the digital cushion. By allowing the hoof to function as nature intended, barefoot horses can maximize the benefits of their digital cushion, promoting overall hoof health and soundness throughout the body. The digital cushion is built through stimulation. It needs to be used to strengthen it, it it is not being used it will atrophy and become weak. This means that a heel first landing and healthy frog are of the utmost importance and should be made a priority by your farrier or trimmer. As advocates for healthy hooves, it's essential to recognize and appreciate the vital role this remarkable structure plays in promoting soundness and comfort for our horses. Understanding the Difference between Laminitis and Founder In the horse world, Laminitis and Founder are often used interchangeably, but they actually mean different things. Let's break it down: Laminitis = Inflammation of the Lamina Laminitis happens when the sensitive lamina around the coffin bone gets inflamed. This includes the sensitive lamina on the front and sides of the coffin bone, as well as the solar corium on the bottom of the coffin bone. Founder = Coffin Bone Rotation Founder occurs when the coffin bone rotates or sinks within the hoof capsule. It can be a small or big rotation, but either way, it's considered foundered. Think of it like being pregnant – you either are or you aren't. Once that hoof wall connection is gone, it has to be regrown from the top down, a long process of about 8 -12 months. It's important to know that a horse can have laminitis without getting founder, and a horse can get founder without experiencing laminitis. While they often go together, it's not a strict rule. Some horses with laminitis progress to founder, but not always. Founder can also happen on it's own, over time due to too long in between trims or improper trimming - this is called mechanical founder. These horses might not show laminitis signs but may seem sore, stiff, or unsound. The great news is most cases of laminitis or founder can be healed. It's a challenging journey, but with a knowledgeable trimmer or farrier, along with some changes to the horse's diet and living conditions, recovery is possible! Understanding Founder and Hoof Healing Founder is a serious condition involving the rotation and potential sinking of the coffin bone within the hoof capsule. It can range from a slight rotation to a severe scenario where the coffin bone penetrates the sole and emerges at the bottom of the hoof. Although the goal is to avoid such extremes, the reality is that founder is a common issue observed in trimming practices. In a foundered hoof, the wall at the coronary band initially displays a healthy angle, even if only for a short distance. As it descends, there is a sudden change in angle, and the wall flares forward. Skilled trimmers and farriers can identify founder, but the degree of rotation requires diagnosis through X-rays by a veterinarian. Sometimes, a hoof wall may flare but not be foundered, this is characterized by a less abrupt angle change and often involves multiple deviations in angle. A flare is simply a stretching of the lamina, while founder is actual disconnection of the lamina. While prompt veterinary attention is crucial during a laminitic event, X-rays are equally important for foundered horses. Collaborating closely with your farrier/trimmer is essential to determine the rotation severity and trim the hoof correctly for pain relief and healthy growth. Though serious, founder is often treatable. A knowledgeable trimmer/farrier is vital, understanding the hoof condition and trimming to alleviate rotation, fostering the growth of a healthy, well-connected hoof wall from the coronary band down. Rehabilitation duration varies, spanning 8-12 months depending on severity and individual hoof growth rates. The key to a successful rehabilitation is maintaining a short toe and reducing leverage on the fragile new growth, preventing excess length that could leverage the lamina apart. A short trimming schedule, typically every 2-4 weeks based on severity, is crucial. I routinely employ this approach in rehabilitating foundered horses, and I often use glue on shoes to provide comfort and soundness during the rehabilitation process. Understanding Laminitis: A Comprehensive Insight into its Impact on Horses Laminitis is a complex condition characterized by inflammation of the sensitive lamina enveloping the coffin bone. This intricate structure involves the sensitive lamina along the front and sides of the coffin bone, as well as the solar corium beneath the bone. The sensitive lamina is a vascular layer covering the coffin bone, equipped with nerves and a blood supply. It intricately intertwines with the insensitive lamina, positioned on the inner side of the hoof wall. Unlike its counterpart, the insensitive lamina lacks a blood supply and nerves, yet its semi-rigid structure provides essential support. The interlocking connection of the sensitive and insensitive lamina acts like Velcro, crucial for maintaining the proper position of the coffin bone within the hoof. When a horse experiences laminitis, the sensitive lamina becomes swollen and inflamed. This inflammation is profoundly painful as there is limited room for expansion between the interlocked insensitive lamina. The severity of laminitis varies; a horse with mild laminitis may exhibit sensitivity when walking on hard surfaces, while severe cases may result in a distinct rocked-back stance as the horse seeks relief from inflamed lamina pressure. Swiftly reducing inflammation and relieving hoof wall pressure through trimming by a knowledgeable trimmer or farrier can often prevent the progression to founder. If left unaddressed in severe cases, the persistent pressure may lead to lamina separation, allowing the coffin bone to rotate and sink within the hoof capsule. It's crucial to emphasize that this progression is not an overnight occurrence but develops gradually, underscoring the urgency of prompt intervention to alleviate inflammation. Laminitis can be triggered by many factors, with carbohydrate overload from lush grass or sudden grain intake being the most common. Other triggers include hormonal imbalances, stress, metabolic issues, systemic conditions, and even improper trimming or repeated concussions on hard surfaces. If you suspect your horse has laminitis, call your vet ASAP, if left untreated it can lead to serious complications. Unraveling Acute Founder: Debunking the Myth In our recent posts about Laminitis and Founder, we've explored the differences and subtleties of these equine hoof conditions. Now, let's delve into the intriguing but incorrect concept of "Acute Founder." Acute Founder, often described as a rapid event - akin to an overnight occurrence, is commonly known (incorrectly) in equestrian circles. However, it's essential to clarify – this phenomenon does not truly exist. In the equestrian world, it's not uncommon for horses to undergo gradual, unnoticed founder over an extended period - this is called mechanical founder. Despite regular hoof inspections, the lack of comprehensive knowledge sometimes leads horse owners, farriers, trimmers, and even veterinarians to overlook the subtle signs of founder. This knowledge gap can be disconcerting, underscoring the need for ongoing education within the professional community. Now, how does this tie in with a scenario where a horse seemingly acutely founders after a grain binge? Let's break it down. In my experience, I've encountered horses where, on the initial visit, I identified signs of founder in their hooves. Surprisingly, these horses were actively performing daily exercises and work, exhibiting no overt signs of soreness or discomfort. Often times the horse owner doesn't understand how anything could be wrong, and chooses to disregard this information. However, dismissing this situation with an "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" mentality is a perilous choice. The consequences of neglecting this metaphorical "ticking time bomb" are substantial. The horse continues its routine, seemingly unaffected, until a day of grain indulgence/hormonal imbalance or some other laminitis trigger, rendering the horse acutely laminitic and unable to walk. When the vet is called, the horse owner, citing the horse's soundness the day before, leads to a common misdiagnosis - Acute Founder. The assumption is that founder occurred overnight due to the laminitis event, when, in reality, it had been quietly progressing for an extended period of time. Similar situations arise, such as a horse progressing well until it develops tenderness in a front hoof. When the vet is consulted, the assumption is that the founder occurred recently. These occurrences, are not rare, and they underscore the importance of understanding the timeline of founder development. While laminitis can, in some cases, lead to founder, the crucial fact is that founder does not transpire overnight. For the lamina to lose its connection and the bone to initiate rotation away from the hoof wall, a gradual process unfolds. As the lamina separate, the cells secrete a liquid form of keratin, creating a lamellar wedge that progressively enlarges over time to fill the growing void between the coffin bone and the hoof wall. As the hoof wall continues to grow, the wedge pushes the wall forward creating the extreme flare we typically associate with foundered hooves. In summary, the notion of a horse acutely foundering overnight is a myth. Founder is a gradual buildup, while laminitis, if promptly addressed, does not necessarily culminate in founder. Continuing to deepen our understanding of these intricate hoof conditions is key to promoting the well-being of our equine friends. For more information check out our

Laminitis and Founder Online Course! I have been trimming for about 15 years now, and my trim has definitely evolved and changed along the way. There are many cases where I don’t trim from the top - if the hoof doesn’t warrant it, but there are a lot of cases that I do trim from the top, and a lot of it, as I specialize in founder rehab. I learned a long time ago, that the best trimmers and farriers (and bodyworkers and trainers and coaches and horsemen), don’t subscribe to a specific method, but stay flexible to adapt to each horse, each hoof, and each moment as needed. I live by the philosophy to never say never or always when it comes to horses, because we are constantly learning and evolving and changing things up.

A lot of the argument I get about trimming from the top is that it thins the hoof wall. And yes, I agree that it does that. In fact, thinning the hoof wall is actually part of what I’m aiming for. Not because I want to weaken the hoof or take away protection, but a thinner wall wears faster, and won’t apply as much leverage if it’s wearing as the wall grows down. And that leverage is another reason I rasp from the top. Every 1/2 inch of length is equal to 50lbs of pressure per square inch, and when a long toe applies pressure on the wall it can lead to flare and lamellar detachment. The biggest thing that I think people need to realize also, is that when we thin the hoof wall by rasping, there is stretched white line or lamellar wedge underneath it, which actually acts as an insulator to the wall, so we are in fact thinning the original wall, but the same amount of protection remains. So to me, there is no debate to be had. I will rasp from the top when flare is present, to reduce leverage on the lamina and the new growth that is coming in. If a hoof has no flare or leverage, then it doesn’t require rasping from the top. I would be absolutely thrilled to have someone show me a case study of a foundered horse that had a lamellar wedge, that was trimmed without ever having the wall rasped from the top, that was successfully rehabbed to have complete lamellar reconnection. Rasping from the top is hard work, and if I could find a way to rehab these horses without doing it, I’d love to save the energy. But the bottom line for me is that I’m in this business to fix horses, and this technique works well for me when used appropriately. This first video shows the trimming of a pretty well maintained "vertical" bar. The second video shows bar that is a bit more "overlaid" or "embedded" and how I would trim them differently. I try not to get too hung up on the "type" of bars, but instead just try to trim the bar to match the solar concavity and to allow the bar to function as it should - to help structure the shape of the back of the hoof and the collateral grooves. .

A horse's hooves are a window into their overall health, and a well-executed barefoot trim can significantly contribute to their well-being. One of the key indicators of a successful barefoot trim is the natural wear patterns that emerge over time. In this post, we'll explore the signs of natural hoof wear and what they reveal about your horse's hoof health. 1. Even Wear Across the Hoof A healthy barefoot trim promotes even wear across the entire hoof. When the weight is evenly distributed, it prevents the development of imbalances that can lead to discomfort and lameness. Check your horse's hooves regularly for signs of symmetry in wear. 2. Smooth and Rounded Edges Well-maintained hooves exhibit smooth and rounded edges. Rough or jagged edges may indicate uneven wear, and addressing this promptly can prevent issues such as chipping and cracking. 3. Sole Callusing Natural hoof wear often results in the development of calluses on the sole. These calluses act as a protective layer, providing additional support and resilience to the hoof. A barefoot trim that encourages the development of calluses contributes to the overall toughness of the hoof. 4. Frog Engagement A healthy barefoot trim pays attention to the frog, allowing it to make ground contact. This engagement is crucial for shock absorption and circulation. A well-trimmed frog should have a consistent texture and should not be overly recessed or protruding. 5. Consistent Stride Length Observe your horse's movement. A horse with a healthy barefoot trim will likely have a consistent stride length, and will land heel first. If you notice changes in stride, toe first landings or any signs of lameness, it may be an indication that the trim needs adjustment.

In conclusion, understanding the signs of natural hoof wear is essential for assessing the success of a barefoot trim. Regular monitoring, coupled with a knowledgeable barefoot trimmer, can ensure that your horse's hooves remain strong, balanced, and resilient. Remember, each horse is unique, and the rate of wear can vary. Consult with a qualified barefoot trimmer to develop a trimming schedule tailored to your horse's individual needs. By paying attention to the signs of natural hoof wear, you contribute to the overall health and happiness of your equine companion. Winter can transform the landscape into a beautiful wonderland, but for barefoot horses, it can present unique challenges. With a pro-barefoot mindset and strategic care, you can ensure your equine friend not only survives but thrives in winter conditions.

The Winter Impact on Barefoot Hooves Moisture Imbalance Embrace the natural moisture regulation capabilities of barefoot hooves. The wetter weather in winter can provide moisture to the hoof that is lost during the dry season. A little bit of moisture is a good thing, too much and we can start to see a weakening of the tubules or potentially a thrush invasion of the frog. Consider products like Artimud to combat or prevent thrush, and Stronghorn to harden the sole if too much moisture is a problem. Slippery Surfaces Turn the tables on slippery surfaces with the added traction of bare hooves. Regular trimming keeps excess length at bay, reducing snow balling up in the hoof. For an extra boost, explore the world of Cavallo Trek hoof boots designed to provide grip without compromising the natural flexibility of the hoof. Boots and composite shoes can be studded for more traction when riding. Proactive Winter Hoof Care: A Barefoot Approach Regular Trims A well-maintained barefoot trim supports the hooves in facing winter challenges head-on. A shorter trim cycle to avoid excess length that will allow snow to ball up is key. If your horse lives on hard, frozen, Icey ground, consider leaving an 1/8th of an inch of extra heel height to provide some extra vertical depth in the hoof. Balanced Diet for Resilient Hooves Feed your horse a nutrient-rich diet to fortify their hooves from within. Adequate nutrition not only supports overall health but enhances the natural resilience of barefoot hooves. Horses need vitamin e in their diet and they get it by grazing on fresh grass or from hay. Did you know that hay loses up to 70% of it's vitamin e content during drying? If your horse doesn't get to graze on pasture during winter, consider supplementing vitamin e in their diet. Hoof Boot Bliss Hoof boots aren't just an accessory, they can provide much needed protection from hard, icy ground. You can use pads inside the boots to help thin soled horses, and studs if needed for better traction. Pro tip: use felt pads, Artimud and Gold Bond Foot powder inside your horse's boots to wick away moisture from the frog to prevent thrush. Active Lifestyle Advantage Maintain a consistent exercise routine. Movement stimulates blood flow, promoting natural hoof health and resilience. Your barefoot horse is designed to move, and winter shouldn't stand in the way. Even light riding or hand walking to keep your horse moving will help. I embrace winter here in Canada and use it to refine my bareback riding and focus on foundational elements of training such as in hand work and really perfecting lateral movements at the walk. Hydration Happiness Ensure your horse stays hydrated, even in colder weather. Proper hydration is the secret weapon in maintaining the strength and flexibility of barefoot hooves. I offer my horses slightly warm water after winter workouts and often will add a dash of apple cider vinegar or unsweetened apple sauce to encourage my horses to drink more. I also like to add a bit of warm water to their grain/supplements in wintertime to increase hydration. Conclusion: Barefoot and Bold in Winter Winter with barefoot hooves is not a challenge to be feared but an adventure waiting to be embraced. Often the snowy landscape offers a reprieve from the muddy season, and helps to keep those furry winter coats clean and fluffy! Empower your horse to not only weather winter but to revel in it. And just think, less snow balls in their hooves, and cleaner coats leads to more time riding and less time grooming! Cheers to a winter of happy, healthy hooves and the joy of barefoot living! Our world is ever changing and the technology and research in the farrier industry is evolving fast. Composite shoes and pads are flooding the market, being manufactured by many different companies around the world. While I am a huge barefoot advocate, I am also an advocate for keeping horses comfortable and sometimes that means they require hoof protection. I am not in favor of traditional metal shoes because in my opinion they are too rigid and limit hoof flexion as well as increase the impact energy of movement (by negating digital cushion function). This impact must then be absorbed by the horse's joints and musculoskeletal system. Metal shoes also peripherally load the hoof (meaning they only weight the outer hoof wall), causing frog and digital cushion atrophy and lack of sole stimulation. Composite shoes are a good alternative as they can provide protection and comfort while still allowing the hoof to function naturally to absorb impact. This is because of their anatomically minded design that incorporates weighting the frog and therefore the digital cushions as well as the sole, bars and hoof wall collectively. [Weighting the whole bottom of the hoof as nature intended] Like traditional shoes, composites can be used in concert with hoof packing, wedges, anti fungal pastes, and be customized to the individual horses' needs and hoof shape. In order to fully understand the benefits that composite shoes can provide we have to understand when they may be a good option for a horse. I see all shoes, boots, pads, casts and hoof protection sources as a band aid approach. This is not a negative thing, but should be seen as a means to an end. In other words we should use these devices to keep the horse comfortable while we are addressing the root cause of the problem (i.e. weak or damaged hooves) so that we can ultimately return proper hoof form and function so that protection is not needed. Horses that have thin soles, disconnected hoof walls, weak frogs and digital cushions, who are foundered or have navicular disease can all benefit from the use of composite shoes. Below are several examples where I have applied composite shoes for various reasons: The most important part of applying a composite shoe is the trim you apply underneath the shoe. This goes for traditional metal shoeing as well. Setting the shoe back to the optimal breakover point is crucial. Leaving excess hoof wall at the toe will allow the toe to migrate forward, leading to under run or crushed heels and a distorted hoof shape. When does a horse need composite shoes? Horses are not naturally flat footed. Flat soles with a lack of concavity come from disconnected hoof walls. Horses that don't have this connection can benefit from composites because they add immediate "false concavity". This concavity provides relief to the inflamed and over stimulated solar corium on the underside of the coffin bone that is commonly seen in flat footed horses. These are typically the horses that are sold as "needing shoes", and are the ones instantly lame when the shoes are pulled. There is a severe breakdown of the hoof capsule and in my opinion it needs to be corrected, by facilitating a proper hoof function via the trim underneath the composite shoe. The horse can then grow in a well connected hoof wall that will in time re-elevate the coffin bone and create the concavity that is needed for soundness barefoot. Horses that have thin soles also benefit from composites. They protect the sole and cause it to thicken by decreasing the wear on it. It is common practice for traditional farriers to "clean up" the sole during a trim, or "carve in concavity", thereby thinning the sole and removing the often ugly but helpful protective outer layer. Routine trimming like this leads to thins and weak soles that are unable to bear weight. Giving the sole a reprieve by using composite shoes call allow it to thicken and then we can transition back to barefoot in a way that allows proper hoof function to actually stimulate more sole growth and an overall thicker, healthier sole. Horses with navicular disease or a weak caudal hoof can also benefit from using composite shoes. The design of the composite shoes I use (Easyshoe Versa product line) incorporate frog support and a thick outer rim that also weights the sole of the hoof. Typically the back of the hoof becomes weak from a lack of proper stimulation. Traditional metal shoes only weight the heels and hoof wall, lifting the frog off of the ground. This lift reduces stimulation on the frog and therefore the underlying tissues of the digital cushion. This lack of stimulation over time can lead to atrophy and degeneration. When the soft tissue starts to fail, the horse usually overloads the toe and avoids weighting the heels, further compounding the problem and this can lead to irreversible damage to the navicular region. Using a composite shoe with sole packing and/or heel padding can often create enough of a cushion that these horses can start to comfortably weight the rear of the hoof again and start to regenerate the soft tissues. Over time you can reduce the padding and sole packing and eventually move from composite shoes back to barefoot. Prioritizing heel first landings is key to this rehabilitation process. I love to be able to utilize composite shoes when needed in my practice. They truly have become a game changer for me. For clients who are not interested in using hoof boots, or horses that require 24/7 support in the beginning of their rehab these shoes can be the difference between soundness and pain. My number one goal of using composite shoes is to return the hoof to it's proper form so that doesn't require protection in the long run. In all actuality everything we can do with composite shoes can be done with some variation of hoof casts, boots and pads, but often the use of the composite shoes is far more convenient for the owner. While my primary goal is to help the horses, I can't facilitate that if I don't keep the owners happy :)

Yes!!!

As a professional trimmer I have seen it all. I have trimmed rescue horses, show horses, race horses, competitive horses and backyard pasture ornament horses. From mini sized to draft sized, there are very few constants in trimming. Hoof shapes and sizes vary, conformation plays a huge part, but I can tell you with 100 percent certainty that the horse who behaves well always gets the best trim. I got into this line of work because I love horses. And it is legitimately my life's mission to help as many horses as possible. However, I have to keep my own personal safety at the top of my priority list when working, or else I may not be able to help any horses if I get hurt. Horse's that kick or strike or bite are a no brainier. These horse's need training before I can work on them, period. I am not a trainer in the capacity of my job as a trimmer, and if you wouldn't pick up it's hooves to clean them, don't call me to come and trim them. You would be amazed at how many clients I have encountered that I have asked "and how is she when you clean out her back hooves?, does she kick?" and to this their reply is "I wouldn't know, I was too nervous to try", or "well she tried to kick me, but I figured with your experience you would be fine". ---> Insert eyeroll here. So when I am dealing with a horse that is dancing around, pulling their hoof away, or any other annoying but not necessarily as dangerous as it could be behavior, I still have to be on guard. This means that sometimes I don't get to stand in the most comfortable position to trim, I don't get to get a thorough look at the hoof to assess balance etc, I have to trim on the fly so to speak and get done what I can in the moment. Accommodating horses because of behavior issues is challenging and it definitely compromises the trim quality. In my experience there is a huge difference between horses that have physical limitations or injuries that make it hard for them to stand for trimming and difficult horses due to behavior. Horses with physical issues aren't trying to get out of trimming, they are just trying to survive and reduce their pain or discomfort. I don't mind contorting myself in order to get them trimmed and keep them comfortable, but ultimately it does mean that they don't always get a complete trim. For instance sometimes horses can't lift the leg high enough for me to hold or use my stand, these horses get a functional trim but I can't be as detailed as I'd like. Functional is key here. I have trimmed horses where I have had to kneel down behind a back leg in order to trim because they had arthritis. I would not put myself in a compromising position like that with an ill behaved horse. Ill behaved horses aren't trying to be difficult, but they don't know better if we don't teach them. As I mentioned above, it is not in my capacity as a trimmer to train client's horses. I am also not the type of trimmer that will "smack a horse" with my rasp or "discipline" a horse (not that I believe this type of discipline is particularly helpful anyway). I believe that correcting these behaviors is the owner's job, and often times when a horse is misbehaving I will step back and look to the owner to correct the problem. When I am training my own horses to stand for trimming their are a few techniques that I use. First let me start off by saying that picking up and holding the hooves has nothing to do with the hooves. This can be a hard concept for people to grasp, but it is a respect issue and not a hoof issue. Moving your horse on the ground is the key to teaching them to stand. Can you circle them, send them out, bring them back, ask them to move their feet faster, slower, stop? You will gain their respect and they will let you be the leader if you can take control of their movement and show them that you are in charge of the space, but that you are fair. When I have a horse that is dancing around and doesn't want to stand I give them a choice. They can choose to stand nicely, or I will ask them to move their feet or do something that requires more energy or thought until such a point that they will choose to stand still. This isn't a punishment, it is a choice. Forcing an anxious bouncing horse to stand still is dangerous, they are bound to explode at some point and it's better to channel that anxiety into movement and getting them back to the thinking side of their brain as opposed to the reaction side. Horses that are stubborn or dominant (read left brained) usually respond well to backing up. Again I offer a choice: they can stand still and let me trim, or we can back up with effort clear across the arena. After one or two back up sessions they usually choose to stand still. I used to trim an Appaloosa and it could take up to an hour to get him trimmed. He would dance around and pull the rope from the owner's hands and run off etc. He generally had poor manners to begin with, and she was a very passive owner who allowed him to take control of the relationship. One day she couldn't be present for the trim and asked me to do it alone. It took me approx. 20 mins start to finish to get him trimmed. This is how I set him up to succeed: First, I attached a long line to his halter instead of a lead rope, and I didn't tie him, I just left the rope on the ground in front of him where I could quickly and easily grab it if he decided to run off etc. Second, every singe time he pulled his foot away or even thought about trying to leave I dropped everything, literally dropped my tools, and backed him up with serious effort about 50 feet. When I say back him with effort I mean quickly and with purpose. No dawdling or lazily drifting backward. And I did not get rough with him, but I made sure he knew that he needed to get out of my space in backward fashion ASAP. After about 3 of these little back ups, he stood like a champ for the trim and every trim after that. He just needed to understand his choices (and boundaries). Trimming is an art form. Understanding the anatomy and function is key, but also being able to physically apply the desired to trim appropriate to the anatomy is the bigger picture. I am constantly trimming, then assessing, tweaking the trim, checking again, etc. And when the horse starts getting impatient and pulling away I may miss a small detail or little assessment that might result in imbalance or unevenness. While I always try to do the best trim possible, there are a lot of factors that can impact the quality of the trim. Having a clean and dry place to work also makes a big difference. Trying to trim wet and muddy/snowy hooves is a nightmare. They are slippery, I can't hold them, and my tools get clogged and jammed. If the horse is short on patience to begin with and every time he takes his foot away he puts it down in mud, I have to then clean it again before I can continue to work. This is frustrating and it also tests the horse's patience as the trim takes longer. I don't need to have a barn or stall to work in, but a simple rubber mat on the ground or a concrete driveway makes a big difference. Toweling off your horse's legs so they aren't caked with mud is also helpful. (Pro Tip: make sure your horse is comfortable standing on the rubber mat before the farrier arrives lol). So the next time that your farrier or trimmer is around, pay attention to how well your horse stands for them and how easily they seem to be able to do their job. If you see any errant behaviors that you could address before their next visit, I'm sure they would appreciate it. And if you see something but aren't sure how to correct it, as your trimmer. They may have an idea for you, or a technique that they have found worked in the past, and I guarantee they will very much appreciate your concern for their safety and ability to perform their job. I hope after reading this article that you understand it is in your horse's best interest to behave well for trimming as they will get a far more detailed and thorough trim if they stand quietly, plus your farrier may come back a second time (wink). When I first started trimming almost 10 years ago there were no fancy job titles like hoof care specialist or hoof care practitioner. There were farriers and barefoot trimmers. The former implied you were a blacksmith that could forge handcrafted shoes and the latter meant you were a horse obsessed hippie that thought all horses should should be barefoot in spite of their soundness. What I wanted to do didn't fit into either category so I decided to call myself a natural trimmer. Wild horses don't get their hooves trimmed every 6 weeks, they wear them off constantly because of their nomadic lifestyle. This is natures way of maintaining balance or what I would call "natural".

Barefoot trimmers back then (and lets be honest even some today) tend to come across as a little bit fanatical. There have been well known trimmers who believed in regular aggressive trimming that made hooves bleed, drastic immediate angle changes to the hoof that left horses sore or caused injury and/or permanent damage and so on. These trimmers also tend to be somewhat overzealous trying to impress their views upon every unsuspecting horse owner they come across. This cult like mentality led to a general resistance in the horse world to the barefoot movement and created a stigma of sorts that all barefoot trimmers must trim aggressively regardless of how it affects the horse. I wanted to separate myself from that stigma and at the same time not confuse potential customers by calling myself a farrier. While it's true that farriers don't just forge metal shoes, but also trim hooves, I didn't want to have to explain over and over again that I was only a "barefoot" farrier. There it is again, that "barefoot" word. Another reason I have an issue calling myself a barefoot trimmer is that I don't think all horses should be barefoot all of the time. Let me explain. While I do believe the hoof is meant to be bare to be healthy, there are situations where a horse's comfort level needs to be prioritized over these beliefs. And really sometimes a weak or distorted hoof requires some intervention/protection to become healthy again so that it can function as nature intended ---> bare. So in saying this there are cases in my business where I use composite shoes, hoof boots or hoof casts to help rehabilitate hoof issues and therefore I cannot say those horses are "barefoot". What I believe is the difference between natural/barefoot trimmers and farriers is that farriers believe the hoof can function optimally with support when fixed with a metal shoe, and natural/barefoot trimmers believe the metal restricts the hoof function and circulation and compromises hoof health. Farriers that use metal shoes routinely restore usability to unsound horses via shoeing and horse owners appreciate this. My concern with is this: if a horse is unsound barefoot due to a weak or compromised hoof and you apply a shoe and the horse walks off sound, did you fix the weakness or just cover it up? There will always be horse owners that prefer the ease of having their horse shod to maintain or "restore" soundness, and I have no issue with that. In this free world that we live in people are lucky enough to be able to choose what works for them and their horse. My approach to the same weak or compromised hoof might be to use a form of hoof protection when the horse needs it, but ultimately I want to restore hoof health and remove the weakness so that the horse doesn't require the shoe/boot/cast etc in order to be sound. So ultimately I chose my own path, and called myself a natural trimmer in order to place myself in between what I saw back then as two camps divided. I like to think of myself as Pat Parelli would say as an "extreme middle of the roadist" in all aspects related to horses. And what that means to me is that I try to never become so overzealous in my views that I cannot appreciate another person's point of view, that I will not press my views upon others fanatically, but will share my knowledge openly when asked. I am also not afraid to continue learning and trying new methods and techniques. As Pete Ramey says, I try to "never say never or always" when it comes to trimming because as soon as you do you will encounter a situation where you end up doing something you never thought you would or straying from your usual tactics in the best interest of the horse. 10 years ago when I decided I wanted to learn to trim my horse there weren't many references or places to go to learn. There were of course traditional farrier programs, but I was looking for more a natural approach. I started with reading books by Pete Ramey, Dr. Stausser and other barefoot pioneers but there wasn't a lot available online. This was back before the evolution of Facebook how-to groups and online courses. I struggled my way through balancing what I was reading with my experiments in trimming my own horses and I found that it was an extreme learning curve. Eventually I sought out help and attended one of those traditional farrier courses. I learned a lot about what I wasn't really interested in at that course, but I also learned to use the tools and how to interact with the horses so it was definitely a valuable resource for me.

What I craved all those years ago was a course that would not only teach the theory and science behind barefoot trimming but would also have a hands on component that could help me to build my skill. After trimming for several years and with the encouragement of Cheryl Henderson of the Oregon School of Natural Hoof Care I was able to put together a program exactly as I had wished for back when I learned to trim in order to help others progress with a less steep learning curve then I had experienced. My ultimate goal has always been to help as many horses as I can in my lifetime and I quickly realized that teaching others how to help horses was the most advantageous way to do that. The 6 day barefoot trimming course that I have developed as gone through much evolution since its initial inception. My first course in 2014 was a bit of trial and error. As I did more courses I was able to refine the process and figure out what parts needed more study time and hands on training by watching the rate at which the students progressed through the program. Now fast forward 5 years and that course is dramatically different then that first one. We have now developed an online course that covers that theory and knowledge base before students even arrive. This gives us more time hands on with the horses and more practice time for students while they can be directly supervised. The hardest part about training people to trim is that I have no control over their practices or techniques once they leave my course. I believe that working with horses in any capacity but especially hoof care requires a constant desire to learn. You must become a perpetual student of the horse in order to continue to evolve your learning and not become overconfident or complacent. My all time favorite quote is "he who thinks he knows the most, has the most to learn" (author unknown). I can't stress enough to students when they leave here that my short introductory course to barefoot trimming is simply a starting point. They must continue to evolve their education and build their knowledge base in order to stay relevant and do their best work for horses. I also offer them access to a Facebook group where they can converse with their peers and reach out to me for support and guidance along the way. The 6 day course is not the end of the road, students can attend again in the future for no additional cost and I have seen this second week bring their skills from basic trimming to significantly more advanced. As I am always learning and attending as many clinics and workshops as I can I am constantly adding new things into my course and changing up the content to reflect new research and theories surrounding the hoof. I make a point to attend as many clinics as possible and to study as many trimming styles as well as traditional farrier research because I believe that no time learning is wasted. This journey to work for horses, as anyone that has horses will tell you, is not lucrative. We put our blood sweat and tears into these animals but the experience of watching them overcome lameness or to be able to rehabilitate them is what keeps me grounded and keeps me going. When it comes to rehabilitating horses, or for me even just owning horses, I approach it with the whole horse in mind. For me my horses are companion animals, riding animals, and animals that I use to facilitate my business. They are also living, breathing beings with their own thoughts, feelings and needs. They make friends, have family groups and form attachments to certain horses, animals and people. My main area of focus in my business is hoof care, but in order to achieve optimal hoof health there are many other areas that must be working properly in order for the hooves to be healthy. DIET Let’s start with the diet. There are many conflicting opinions on the optimal diet for our horses. I have taken several equine nutrition courses, been to many seminars and done plenty of research. What I have found is that individual horses needs vary so a one size fits all approach doesn’t work. This post isn’t about nutrition specifically so I will try to keep it short. Up until recently I had a specific combination of feeds and minerals that I fed my herd of 10 on a daily basis. I was feeding each feed or mineral for a specific reason that I had predetermined that the horses needed. I was feeding those minerals because of what I had learned about minerals and hoof health. How did I come up with the theory that they needed them? Well I had read, researched or had been told by a trusted source that they needed them. I had never seen any reason in my horses’ outward appearance, behaviour or apparent health that made me think there was a deficiency, but I assumed like most people do that they should be supplemented with something and therefore I built my list of supplements and off I went to the feed store. I fed these things for years until just this past spring when I heard something that interrupted my thought pattern. I had scheduled an osteopathic treatment for two of my horses with Dr. Laura Taylor and it was while in deep discussion with her about equine diets and nutrition that she said something that has stuck with me ever since. She said “if you are feeding or supplementing your horse with something, you should see some type of result”. Weather those results are physical, such as seeing an improvement in their hair coat or outward appearance, emotional, such as seeing less anxiety or behavioural problems, or internal, such as something affecting the organ systems in the body or the musculoskeletal system causing stiffness or even lameness. The point is you should see some type of result from what you are feeding, or you should see a result of not feeding it... This caused me to rethink my horses diets and cut out everything but pasture and hay for three months. What I found was that there was no change in them. Their hair coats were still beautiful and shiny, their hooves were still brilliant and they were still emotionally sound and happy. The moral of the story for me was to keep it simple. And I’m not saying all horses don’t need supplements, but what horse owners need to do is understand what they are feeding and to make sure it is necessary for your horse before blindly feeding something just because someone else does, someone told you to, or because of some fancy packaging. I have now started to include some new supplementation to the hay and pasture diet of my herd, more about this in an upcoming BLOG that will be dedicated to nutrition MOVEMENT = LIVING ENVIRONMENT After looking at the diet I also want to address the horse’s living environment. Does he stand around in a stall all day, a small paddock, or a pasture or larger open area? Is he alone or kept with others? What those things mean to me is does the horse get enough movement to fulfill his physical and mental needs? Does he have herd mates to fulfill his social and emotional needs? Does his paddock have an enough varied terrain to adequately stimulate his hooves? This is maybe the most important part to me. My horses live in a herd, on a track based paddock system. They have access to pasture when needed and are constantly on the move. I can regulate their feed and movement as required. None of my horses get “hot” because they are standing around all day, and they don’t get bored because their social and emotional needs are fulfilled. None of them need a “job” or need to be ridden in order to keep their cool. They live like horses, and yet I can ride and play with them as needed. I have very few instances of cribbing or pacing or any other bad habits. Those are byproducts of emotional stress that doesn’t exist in my herd. Making sure the horse’s living environment is conducive to a happy and healthy horse is important because then they are able to keep physically fit and engaged which will help with the healthy hooves we want to grow DENTAL HEATH = BALANCE Another huge factor is teeth. I recently went to Florida to further my knowledge and become a graduate of the Horsemanship Dentistry School. This was so important for me as I have always known there was a connection between what was happening in the mouth and the soundness in the body but I needed more information. What I learned was so mind blowing. An imbalance in the teeth will create an imbalance in the jaw that would translate to an imbalance in the neck, shoulders and feet. An imbalance on the front end will affect the hind end and so on. It becomes a cascade effect, and the best part is when I am able to feel an imbalance in the mouth, correct it and see a direct improvement in how the horse moves or behaves. Horses are so innately in tune with themselves that even just a slight dental problem can have a big effect. The dentistry school I went to teaches manual balancing without the use of sedation so that you can watch the horse respond to the changes you make. I have never quite done anything else as intimate and rewarding with my horses as putting my hand inside their unrestricted mouth. With no speculum to protect me, and no sedation to alter their state of mind, I can remove any sharp points inside their mouths and watch them lick and chew and feel the area with their tongue. That is usually followed by them pressing their head into my chest with thanks. No joke, this just gets my heart pumping. EXERCISE = MUSCLE The last thing I will touch on in our whole horse approach to health is riding and the subsequent muscle development. Riding can play a huge part in the health of your horse’s hooves. For instance, a balanced horse that is ridden round (not over bent) will be travelling in balance from the front end to the hind end and engaging their core muscles and therefore loading their hooves optimally. A horse ridden hollow or unbalanced will create unbalanced forces on the hooves and therefore may not wear evenly. A horse ridden very over bent will travel with too much weight on the front or hind end and not travel in a balanced manner. How the horse is conditioned to riding will also affect how he will move in the pasture or paddock. Wild horses are conditioned to move 20-40 miles per day on varied terrain and tend to build well balanced bodies and hooves. When we keep horse in domestication we inhibit their ability to move freely and they don’t always understand how to move properly because of this. We must teach them how to carry the weight of a rider and still move in balance and harmony. HEALTHY HOOVES = HEALTHY HORSES

Expectations – Having realistic expectations is very important when transitioning your horse from shod to barefoot. Expecting your horse to perform the same way barefoot as they have in shoes is unrealistic. It takes time to strengthen and built hoof health and often times the shoeing process over many years has caused much damage within hoof. It is very much the same as asking a seasoned marathon runner to compete without their running shoes. It would be uncomfortable for them to feel the hard or rocky ground under their sensitive feet for the first few times. However, given enough time the marathon runner could build adequate callous so that he could perform barefoot. Taking horses barefoot should be about the long term health of the horse, not the rider’s short term performance goals. This being said, we must still make sure that our horses are comfortable when transitioning by providing them with hoof boots when needed and correct and frequent natural trims. Time - A hoof that has been in shoes for extended periods will take time to heal internally as well as externally. Perpetual shoeing cycles can cause contraction and atrophy of the internal energy dispersing structures of the hoof. A horse that is shod is peripherally loading the hoof, which means that only the outside rim of the hoof is impacting the ground. This causes the frog and digital cushion (a structure paramount to a healthy barefoot hoof) to atrophy and weaken. However the good news is that the digital cushion has tissue similar to stem cells within it, and given the right opportunity (ie a balanced natural trim with proper stimulation) it can regenerate. The other problem with shoes is the lack of flexibility within the hoof. A metal horse shoe cannot expand and contract like a natural hoof does so there is less flexion and movement within the hoof. Less flexion and movement results in decreased blood flow and energy dissipation leading to further tissue damage. Upon pulling the shoes and providing a natural trim circulation and flexion are immediately restored, often resulting in temporary minor discomfort for the horse as circulation is increased and blood flow is restored back to a normal state. Environment – A barefoot horse’s living environment plays a large role in strengthening their hooves. A horse that lives on soft pasture will have a hard time building the callous needed to ride on a rocky trail without some form of hoof protection. Whereas a horse that lives on hard rocky ground will have no trouble travelling on a rocky trail as his hooves would have already been conditioned to it. Even if all you have for your horse is soft pasture or dirt, adding some river rock around water troughs or in shelters or a favorite hangout spot can be a big help. Exposure to varying surfaces is important in conditioning the hoof and building strength.

Deciding to take your horse barefoot can be a complex decision. While it is greatly beneficial to them to restore natural hoof function, you must make sure you are ready to face the challenges involved with the transition. I suggest you speak with your hoof care provider about the factors mentioned above as well as discuss the overall health of your horses’ hooves and the expected length of the transition period. Published in Saddle Up Magazine June 2015 Time is precious and a healthy relationship with your hoofcare provider is crucial to your horse’s wellbeing. Here are a few tips of what you should expect from your provider and what he/she is hoping to see from you. Be on time. This works both ways as everyone’s time is valuable. If your appointment is scheduled for 1pm, arrive early to prepare your horse and his surroundings for the visit. Do not arrive at 12:59pm just ahead of the trimmer and rush to halter the horse and scramble to get him ready. Instead have your horse haltered and waiting calmly, perhaps lunged if they are in a particularly anxious mood or have trouble standing still. A trimmers schedule can change throughout the day, so please allow them a little bit of leeway. Perhaps a 15 minute window surrounding the appointment time. Anything more than that and they should call to touch base and see if your schedule is flexible. If you or your trimmer are unable to make the appointment at least 24 hours notice is necessary, 48-36 hours is better, but the situation might not always allow. Be prepared. Having the feet picked out is a nice treat and even having the horse lightly groomed should impress your trimmer. I am not stating that your horse be groomed as if they were to beshown immediately following the trim, simply if the legs and hooves are muddy, perhaps curry them off. Your provider likely has several other horses to see after you and would like to stay as presentable as possible. Have your horse on a clean, flat dry surface if possible. A barn isle way, a stall mat, or even just a flat packed dirt area or driveway. Being able to assess the hoof while on the ground is a key component formulating a trimming plan and will make your provider’s job easier. Trying to see hooves in tall grass or mud can be difficult. Your trimmer should also arrive prepared with all of the tools required, and ready to work. Stay in the moment. Be aware of your horses’ behaviour while being trimmed. Being firm and fair with your horse is important in keeping your trimmer safe while they are doing their job. Do talk to your trimmer, but also pay attention while holding your horse so that you can alert the trimmer to a potential spooking hazard or you can let them know if your horse is uncomfortable in a specific position. A horse that is moving around and distracted can be hard to trim, so keeping them focussed on the task at hand is important. If you are unsure how to handle the horse in a given situation, ask your trimmer how they would like you to handle the horse while they are working underneath him.

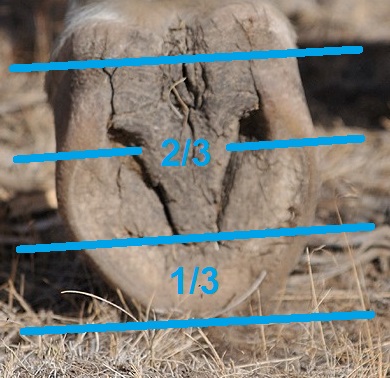

Communication is key. Expressing any concerns or questions you have regarding the trim is very important. An open line of communication will ensure you are both working in the best interests of the horse. Your trimmer should be open to answer your questions, and also explain how or why they are doing things the way they are if you ask them to. The answer of “because that’s how it’s done”, is not acceptable. Payment is due when services are rendered. If you are hoping to pay at a later date or with a postdated check, please consider asking your trimmer if this is appropriate prior to the appointment. With technology today a lot of mobile services are set up to take credit or debit on the spot. However not all have these devices so please check at the time you book your appointment if that is how you intend to pay. Your trimmer should also be prepared to write you a receipt should you require one, and the amount owing should not be more than quoted to you when the appointment was booked unless it was discussed before or during the trim. This occasionally happens if the condition of the hooves require something extra that the trimmer couldn’t anticipate prior to the appointment. Published in Saddle Up Magazine in two parts, April 2015 and May 2015 Nature seems to have a way when it comes to getting things right. The mathematical simplicity that exists when you break a hoof down into sections is quite amazing. At the Okanagan School of Natural Hoof Care we teach a trimming method called the Hoof Print Trim. This method was created by Cheryl Henderson, founder of the Oregon School of Natural Hoof Care. The Oregon School was the first of its kind in North America. A center devoted to the practice of Natural Hoof Care and a better life for our equines. Cheryl Henderson has spent many decades developing and researching her method and has proven it again and again with thousands of dissections and case studies. Our program teaches this method and also relies on the ability to “read” the hoof and each horse’s specific conformation to adapt the trim to their needs. This system allows us to teach the fundamentals of trimming in a short time frame. The formula of a healthy hoof is as follows: the width at the fulcrum (widest point on the bottom of the hoof) equals the length heel to toe. This means that the hoof should be a perfect circle, hind hooves abide by this measurement also but the hoof tends to be more spade shaped. The frog should equal 2/3 of the solar view of the hoof from the back to the front, the remaining sole to the dorsal (front) hoof wall is the other 1/3. The hairline should be at a relaxed 30 degree angle to the ground. All hooved animals have a naturally occurring 30 degree hairline that only becomes distorted through genetic defect, altered living environments and lack of movement, or human trimming error. These formulas have been proven again and again through the study of wild horses’ hooves and as well through countless dissections and case studies. Even the most distorted hoof shapes follow these parameters and can often be brought back into balance in just a few trims depending on the severity of the distortion. This does not mean however that we just measure and cut. These guidelines must be paired with our “reading” of the hooves’ clues to help us determine each horses’ needs. For instance some horses have club feet, therefore this physical deformity will impact the heel height and the angle of the hairline. This is where reading the hoof and determining the best approach for each specific horse is extremely important. A deformity like club foot can sometimes be corrected or improved, but many times is just something you have to work with and adapt your trim around. The Hoof Print Trim is a great starting point for those learning to trim because you can measure and draw where the healthy hoof should be and then train your eyes to “read” the hoof and evaluate using both sets of clues where you should trim. This method starts with evaluating the baseline. The baseline is the rearmost part of the hoof, where we will trim our heel height down to as well as where we take our measurement from heel to toe after establishing the width at the fulcrum. To find our baseline we measure from the back of the heel bulbs at the hairline to the collateral groove exit. On most average sized horses this measurement equals 1 ¼ inches. It varies for ponies or smaller horses and the taller horses and drafts but this is just an average, and again not a measurement we would simply just cut without “reading” into the rest of the hoof first and accounting for and deformities or pathologies etc. After establishing the correct baseline by evaluating the frog health, the periople wear marks, the heel surface, and sole thickness in switchback at the rear of the hoof, we can measure our fulcrum to establish our toe length. The fulcrum is simply the widest part on the bottom of the hoof. It is almost always about ¾ inch behind the apex of the frog occurring at the mid-point of where the coffin bone sits inside the hoof and is not usually distorted by flaring or stretched lamina. We measure the fulcrum from the golden line on one side to the golden line on the other side, not from wall to wall. If the measurement was 4 ½ inches, we would then measure from our baseline forward 4 ½ inches and mark where our golden line should be at the toe. In a balanced hoof that has been trimmed regularly and correctly, this mark will line up with the golden line at the toe. I just want to reiterate that this is also not a cut line, we still have to add our wall thickness to determine where the cut line will be. We also must “read” the hooves’ wear patterns and toe callous before deciding where to cut. Now that we have determined the circumference of the hoof we can establish the 2/3 to 1/3 balance. The baseline to the apex of the frog should be 2/3 of the overall hoof length. Frogs can get stretched forward into the sole’s 1/3 and occasionally need to be trimmed back. This measurement will determine if the frog has migrated forward. However all of our measurements to this point would be inaccurate if we had measured our baseline wrong, so caution must be taken to measure correctly and confirm we are right by reading” the clues and wear marks in the hoof. After establishing the baseline and the heel height we must determine the length of the toe. We do not use the white line as a determining factor as it can stretch and migrate forward giving a false location for the toe length. In order to determine the proper length we measure the fulcrum width from white line to white line on either side of the hoof. A front hoof should be the same width as length. So if the fulcrum is 4 ½ inches from white line to white line then our measurement from the baseline at the rear of the hoof to the toe would be 4 ½ inches. This is not a cut line though, we still have to add the thickness of the hoof wall to this measurement. A lot of times in a run forward hoof the white line can stretch forward and this measurement can seem extreme. However even though the wall flares forward and the white line stretches, the internal structures do not move or migrate. The coffin bone can rotate and sink lower in the hoof capsule in a laminitic or foundered horse, but even in those cases the geometrical mapping will establish the location of the coffin bone before we start to trim and we can work to bring balance back to the hoof. Another factor we have to consider when aligning the bones of the hoof and lower limb is the hairline angle. All hooved animals in nature have a 30 degree hairline in their natural environment (barring rare genetic defects) and the horse is only an exception when trimmed and managed ineffectively. Studies of wild horses in the US Great Basin have shown that when allowed to naturally wear their hooves in their wild environment they almost always have a 30 degree hairline. The few horses with this exception have a genetic defect of a club foot. A club foot is a coffin bone with a steeper dorsal angle and therefore creates a hoof with a steeper dorsal hoof wall angle and a higher heel. Both of these pathologies will affect the hairline angle.

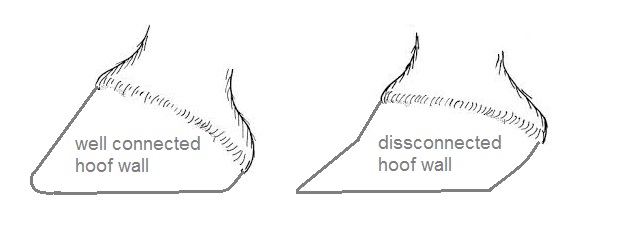

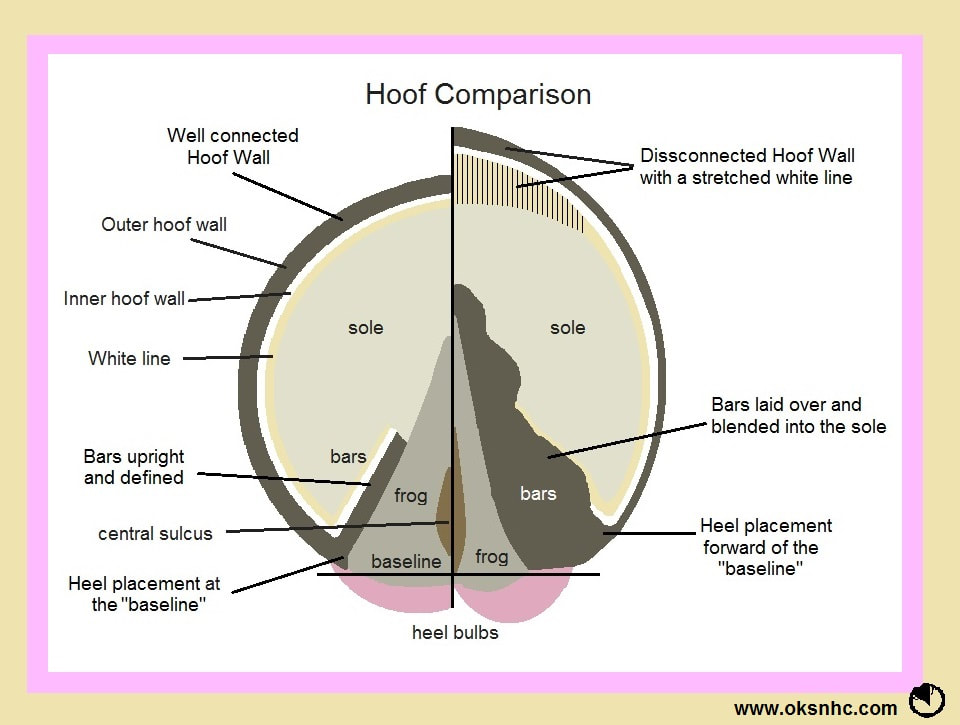

After evaluating the baseline, the fulcrum, the toe length and the hairline angle, we finish our trim by defining and trimming the bars and putting the mustang roll on the front of the hoof. The bars function is for support in the rear of the hoof and it is important that they are not over trimmed, however they must also not be left to grow over the sole as they can cause bruising and abscessing. A mustang roll is a rounding of the hoof wall at the toe to remove any leveraging forces on the hoof wall and to create a smoother breakover. The mustang roll is one of the defining differences between a barefoot trim and a traditional farrier trim. published in Saddle Up Magazine March 2015 #1, Trims Frequent trimming is the most important step in building and maintaining healthy hooves. The average horse should be trimmed on a 6 to 8 week schedule. This can be varied slightly depending on the time of year and how fast the hooves are growing. It also depends on the amount of movement and exercise the horse is getting over varied terrain. Anything more than an 8 week cycle is just damage control and will not facilitate the growth of a healthy strong barefoot hoof. During rehabilitation trimming of damaged and sensitive hooves, the frequency of trims can vary anywhere from once per week to every 4 weeks depending on the situation. #2, Movement Even with frequent trimming practice, a horse will not develop strong hooves without movement. Wild horses in the US Great Basin have been documented to travel up to 40 miles per day in search of food, water and shelter. In contrast our domestic horses usually live in paddocks where they are fed next to their water and do not have to travel far for shelter. One of the best things we can do for our horse’s hooves and wellbeing is to keep them in a herd on a track based paddock system. A track based system where horses are fed throughout the track encourages horses to move on average 7 times father then they would in an open paddock. For more information on this type of horse keeping I would urge you to read Jaime Jackson’s book, Paddock Paradise. #3, Terrain Movement is key, but movement on varied terrain is plays an important role in hoof strength. A horse that lives in a soft grass paddock and only works in a sand arena will not be able to callous his hooves to be comfortable on hard packed ground or rocks. The best way to condition your horses’ hooves is to bring the surface you want them comfortable to ride on into their paddock. That means you can bring in river rock, pea gravel, and road crush gravel. Putting these materials around areas your horse frequents is key. You don’t have to do your entire paddock in them. Placing them around the water trough, or in their shelters is a good way to ensure exposure to those surfaces. At first the horse might be uncomfortable, but over time their hooves will start to callous and strengthen and they will become able to traverse those surfaces without discomfort. #4, Diet A low carbohydrate and high fibre diet is essential for hoof health. It is also important to make sure your horse’s diet is balanced in vitamins and minerals. A diet rich in carbohydrates can cause sensitivity in the hooves, poor horn growth and laminitis. Horses are designed to forage 14-16 hours per day. The best way to feed our domestic horses is by slow feeding. There are many great feeders and nets on the market to simulate natural grazing. #5, Time Patience is key in rehabilitating damaged hooves as well as forging strong healthy barefoot hooves. It takes time to build callous, and to condition the hoof to the environment. Rehabilitation also takes time as you cannot always achieve your trimming goals for a specific horse in one trim. Soundness is key when trying to build healthy hooves and the horse’s comfort must always be a priority. Published in Saddle Up Magazine February 2015 For many horse owners, evaluating and trimming their horse’s hooves is a task left up to their farrier/trimmer. But how do you know that the person that you have hired is doing a good job? You have to be able to evaluate your horse’s hooves beyond the scope of how sound the horse moves. While soundness in the present is important, the horse’s long term hoof health is also a major factor owners must consider. I see many cases where long term incorrect hoof shape or function has lead to irreversible damage while the horse appeared sound until it was too late to correct. However I also see a lot of horses that I am able to rehabilitate and return to use after a deformed hoof has broken down. There are 5 key points horse owners can use to evaluate their horses’ hooves: Heel Placement – The heels should be positioned at what we call the baseline. The baseline is an invisible line that runs across the back of the frog and collateral grooves, and in a well-trimmed hoof also aligns with the heels rearmost surface. When heels are allowed to overgrow or migrate forward from this line, the balance of the hoof is distorted and excess stress and tension is placed on the horse’s joints, tendons and ligaments. Long or forward heels can also shorten stride length. Frog Integrity – When a horse moves forward, their natural stride should allow them to land heel first. If the heels are in the correct position as mentioned above, the heels and frog will contact the ground simultaneously. The frog’s primary function is to protect the digital cushion. The digital cushion lies underneath the hard calloused frog and is a large pad of fatty tissue. The digital cushion absorbs impact and dissipates energy. If the frog is infected with thrush or bacteria, or underdeveloped from long heels keeping it elevated and not touching the ground, this portion of the hoof’s function cannot be performed. Without the energy dissipation of a healthy frog and digital cushion excess stress is placed on the horse’s joints. Wall Connection – A well connected hoof wall supports the coffin bone and allows the hoof to function as intended. The hoof wall grows downward from the coronet to the ground and should not flare or deviate in angle as it descends. A hoof wall that changes its angle part way down the hoof will have a poor connection and decreased concavity in the sole. A disconnected wall can lead to the coffin bone sinking down into the hoof capsule causing inflammation in the sole resulting in sensitive hooves. Sole Thickness – Sole thickness is key to soundness and comfort. A thick sole protects the coffin bone and pads the hoof. The sole should be firm and calloused, you should not be able to flex it when pressing with your fingers. It should have a smooth appearance, and it should have a slight concavity. Concavity varies for each individual horse dependent on their coffin bone shape but the bottom of the hoof should not be flat. A flat hoof signals a balance issue, perhaps in the wall connection or a problem with overgrown bars.

Bar Definition – The purpose of the bars are to support the back of the hoof upon impact. The bar is an extension of the hoof wall as it wraps around from the heel surface. The bars should run at a downward slope from the heel to the mid-point of the frog. The bar should also be upright and defined, not laid over or blended into the sole. When bars invade the sole it can cause many different issues, the most common are: sensitivity on hard ground and reoccurring abscessing. In rare cases embedded bar can also cause navicular like symptoms. Horse owners must learn to recognize what a healthy hoof looks and functions like. Hoof care is a fundamental component of horse ownership and you must know how to recognize a problem before it causes long term damage. Published in Saddle Up Magazine November 2014