|

Yes!!!

As a professional trimmer I have seen it all. I have trimmed rescue horses, show horses, race horses, competitive horses and backyard pasture ornament horses. From mini sized to draft sized, there are very few constants in trimming. Hoof shapes and sizes vary, conformation plays a huge part, but I can tell you with 100 percent certainty that the horse who behaves well always gets the best trim. I got into this line of work because I love horses. And it is legitimately my life's mission to help as many horses as possible. However, I have to keep my own personal safety at the top of my priority list when working, or else I may not be able to help any horses if I get hurt. Horse's that kick or strike or bite are a no brainier. These horse's need training before I can work on them, period. I am not a trainer in the capacity of my job as a trimmer, and if you wouldn't pick up it's hooves to clean them, don't call me to come and trim them. You would be amazed at how many clients I have encountered that I have asked "and how is she when you clean out her back hooves?, does she kick?" and to this their reply is "I wouldn't know, I was too nervous to try", or "well she tried to kick me, but I figured with your experience you would be fine". ---> Insert eyeroll here. So when I am dealing with a horse that is dancing around, pulling their hoof away, or any other annoying but not necessarily as dangerous as it could be behavior, I still have to be on guard. This means that sometimes I don't get to stand in the most comfortable position to trim, I don't get to get a thorough look at the hoof to assess balance etc, I have to trim on the fly so to speak and get done what I can in the moment. Accommodating horses because of behavior issues is challenging and it definitely compromises the trim quality. In my experience there is a huge difference between horses that have physical limitations or injuries that make it hard for them to stand for trimming and difficult horses due to behavior. Horses with physical issues aren't trying to get out of trimming, they are just trying to survive and reduce their pain or discomfort. I don't mind contorting myself in order to get them trimmed and keep them comfortable, but ultimately it does mean that they don't always get a complete trim. For instance sometimes horses can't lift the leg high enough for me to hold or use my stand, these horses get a functional trim but I can't be as detailed as I'd like. Functional is key here. I have trimmed horses where I have had to kneel down behind a back leg in order to trim because they had arthritis. I would not put myself in a compromising position like that with an ill behaved horse. Ill behaved horses aren't trying to be difficult, but they don't know better if we don't teach them. As I mentioned above, it is not in my capacity as a trimmer to train client's horses. I am also not the type of trimmer that will "smack a horse" with my rasp or "discipline" a horse (not that I believe this type of discipline is particularly helpful anyway). I believe that correcting these behaviors is the owner's job, and often times when a horse is misbehaving I will step back and look to the owner to correct the problem. When I am training my own horses to stand for trimming their are a few techniques that I use. First let me start off by saying that picking up and holding the hooves has nothing to do with the hooves. This can be a hard concept for people to grasp, but it is a respect issue and not a hoof issue. Moving your horse on the ground is the key to teaching them to stand. Can you circle them, send them out, bring them back, ask them to move their feet faster, slower, stop? You will gain their respect and they will let you be the leader if you can take control of their movement and show them that you are in charge of the space, but that you are fair. When I have a horse that is dancing around and doesn't want to stand I give them a choice. They can choose to stand nicely, or I will ask them to move their feet or do something that requires more energy or thought until such a point that they will choose to stand still. This isn't a punishment, it is a choice. Forcing an anxious bouncing horse to stand still is dangerous, they are bound to explode at some point and it's better to channel that anxiety into movement and getting them back to the thinking side of their brain as opposed to the reaction side. Horses that are stubborn or dominant (read left brained) usually respond well to backing up. Again I offer a choice: they can stand still and let me trim, or we can back up with effort clear across the arena. After one or two back up sessions they usually choose to stand still. I used to trim an Appaloosa and it could take up to an hour to get him trimmed. He would dance around and pull the rope from the owner's hands and run off etc. He generally had poor manners to begin with, and she was a very passive owner who allowed him to take control of the relationship. One day she couldn't be present for the trim and asked me to do it alone. It took me approx. 20 mins start to finish to get him trimmed. This is how I set him up to succeed: First, I attached a long line to his halter instead of a lead rope, and I didn't tie him, I just left the rope on the ground in front of him where I could quickly and easily grab it if he decided to run off etc. Second, every singe time he pulled his foot away or even thought about trying to leave I dropped everything, literally dropped my tools, and backed him up with serious effort about 50 feet. When I say back him with effort I mean quickly and with purpose. No dawdling or lazily drifting backward. And I did not get rough with him, but I made sure he knew that he needed to get out of my space in backward fashion ASAP. After about 3 of these little back ups, he stood like a champ for the trim and every trim after that. He just needed to understand his choices (and boundaries). Trimming is an art form. Understanding the anatomy and function is key, but also being able to physically apply the desired to trim appropriate to the anatomy is the bigger picture. I am constantly trimming, then assessing, tweaking the trim, checking again, etc. And when the horse starts getting impatient and pulling away I may miss a small detail or little assessment that might result in imbalance or unevenness. While I always try to do the best trim possible, there are a lot of factors that can impact the quality of the trim. Having a clean and dry place to work also makes a big difference. Trying to trim wet and muddy/snowy hooves is a nightmare. They are slippery, I can't hold them, and my tools get clogged and jammed. If the horse is short on patience to begin with and every time he takes his foot away he puts it down in mud, I have to then clean it again before I can continue to work. This is frustrating and it also tests the horse's patience as the trim takes longer. I don't need to have a barn or stall to work in, but a simple rubber mat on the ground or a concrete driveway makes a big difference. Toweling off your horse's legs so they aren't caked with mud is also helpful. (Pro Tip: make sure your horse is comfortable standing on the rubber mat before the farrier arrives lol). So the next time that your farrier or trimmer is around, pay attention to how well your horse stands for them and how easily they seem to be able to do their job. If you see any errant behaviors that you could address before their next visit, I'm sure they would appreciate it. And if you see something but aren't sure how to correct it, as your trimmer. They may have an idea for you, or a technique that they have found worked in the past, and I guarantee they will very much appreciate your concern for their safety and ability to perform their job. I hope after reading this article that you understand it is in your horse's best interest to behave well for trimming as they will get a far more detailed and thorough trim if they stand quietly, plus your farrier may come back a second time (wink).

1 Comment

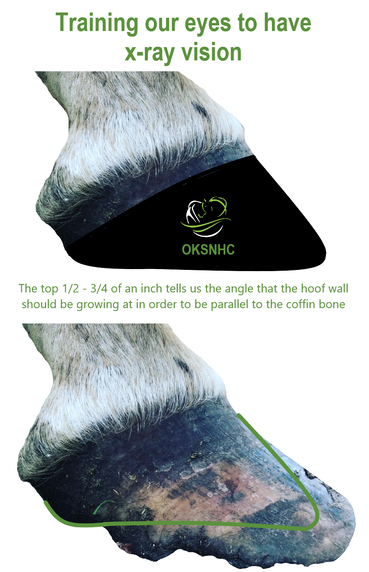

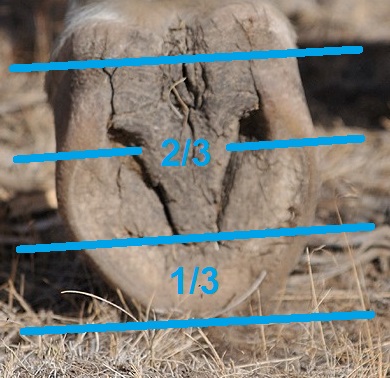

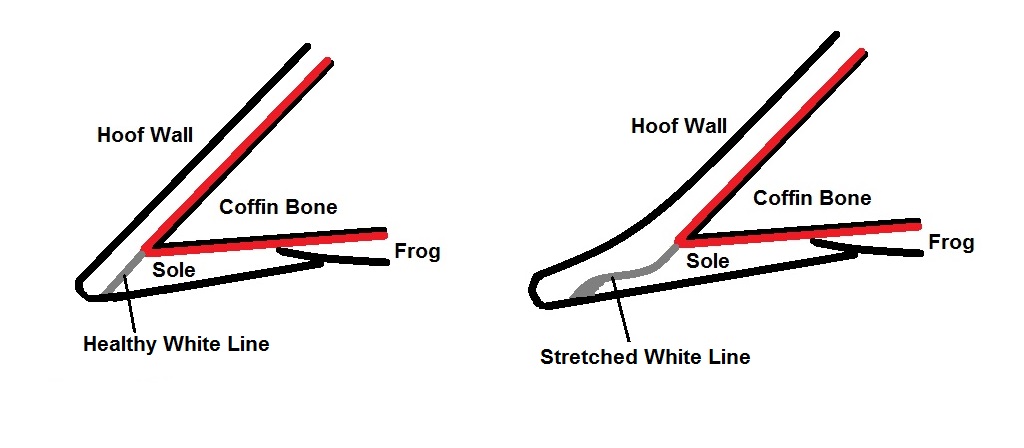

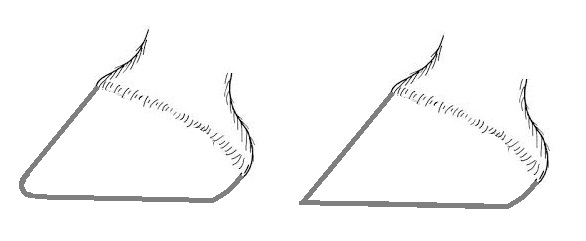

Montana is a paint mare that presented with a disconnected hoof wall, and both rotation and sinking of the coffin bone. She has an extremely flared hoof capsule and a very flat sole with zero concavity. Her owner repots that she is tender when ridden barefoot and "requires shoes or boots" when ridden to keep her sound.

|

AuthorKristi Luehr is a barefoot trimmer/farrier, author, and founder of the Okanagan School of Natural Hoof Care. She is certified by the Canadian Farrier School as well as the Oregon School of Natural Hoof Care, and also has certification in equine massage and dentistry. Her focus is to educate owners about hoof anatomy, function and proper barefoot trimming that supports and grows healthy and functional hooves specific to each horse's individual needs. She is the author of three online courses specific to hoof care and is always striving to create more educational content for students to learn from. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed